Frankly speaking, the conflict of interests between Ukraine and Russia arguably stretches back to when they were united under the Soviet Union and later separated, with the Euromaidan Protests in 2014—now better known as the Revolution of Dignity in Ukraine—being the peak of the hostilities.

Although it seems like things have calmed since then, after the invasion of Donbas and the annexation of Crimea, low-intensity conflicts have been ongoing throughout the years.

In a simpler metaphor, the conflict between Ukraine and Russia is essentially a powder keg that was slowly filling up again with more gunpowder.

Now, all it requires is a single spark to explode.

Situation at the Ukraine-Russia Borders

According to US Intelligence reports in December 2021, as many as 100,000 Russian troops have amassed at the Ukrainian border, despite multiple warnings issued by the United States (US) President Joe Biden and the European Union (EU).

With the number of troops gathering, it was said that Russia could begin a military offensive as early as 2022.

Similarly, in late 2021, satellite photographs have shown that Russian hardware—including self-propelled guns, battle tanks and infantry vehicles, were on the move at a training ground roughly 300km away from the borders.

Ukrainian Defence Military’s latest intelligence assessment said that there were an additional 27,000 troops near Ukraine, with 21,000 air and sea personnel transferring more Iskander operational-tactical missiles to the borders.

The 9K730 Iskander is a mobile short-range ballistic missile system, armed with several conventional warheads including a cluster munitions warhead, a fuel-air explosive enhanced-blast warhead, a high explosive-fragmentation warhead, an earth penetrator for bunker busting and an electromagnetic device for anti-radar missions.

In a nutshell: it is a state-of-the-art military weapon that is a force to be reckoned with, and its presence is very unwelcome at the borders.

Researchers tracking social-media footage have also spotted numerous signs of additional Russian military equipment being shipped westward by train from Siberia, to say nothing of how most of its military camps are based near the west of the country.

Analysis shows that should Moscow desire to push everything into war efforts, it could easily double the number of troops it has at its borders.

However, if you think that is the only military front that Ukraine has to deal with, think again.

The Hotspot Called Donbas

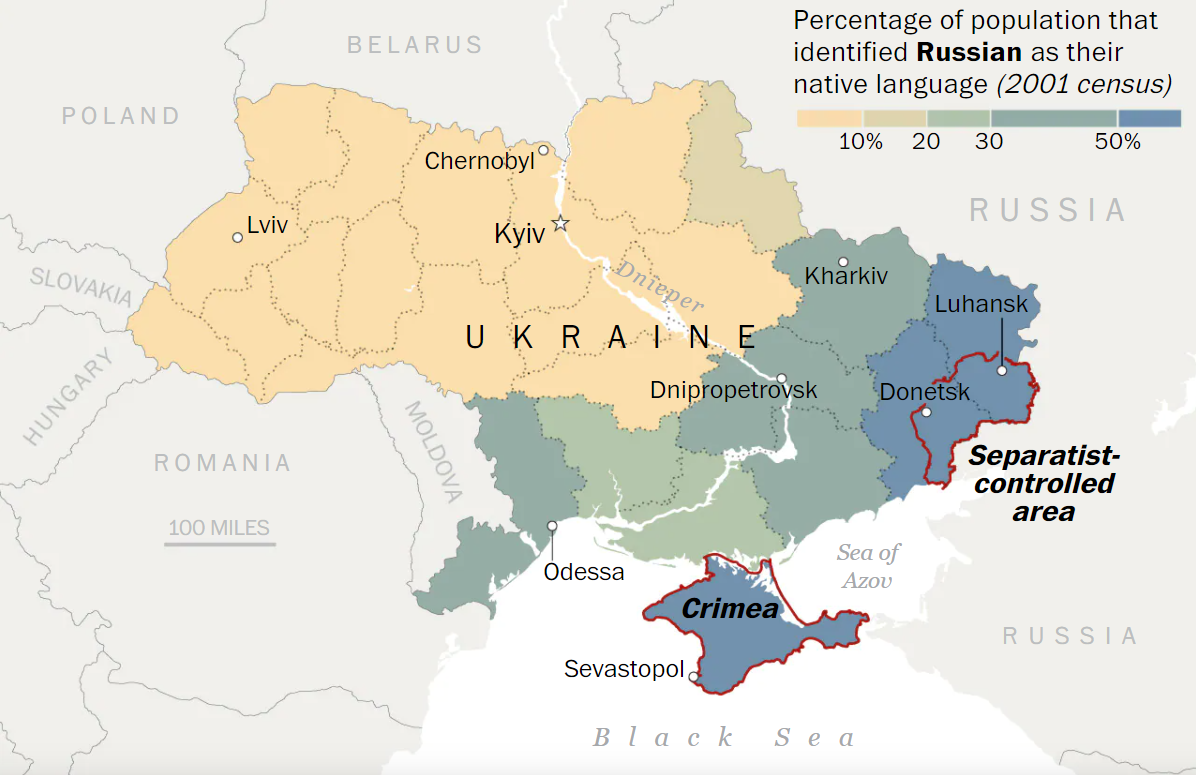

During 2014, an armed conflict broke out in eastern-Ukraine in the Donbas region, an area that is between Donetsk and Luhansk.

While the then-President Viktor Yanukovych was failing in dealing with the Euromaidan Protests in Ukraine’s capital of Kyiv, anti-government separatist groups backed by Russia were also leading armed protests in the Donbas region.

The separatists’ group even went as far as self-declaring Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republic respectively, with every intention to secede from Ukraine and establish its own nations.

Russia initially took a “hybrid approach” where it deployed a combination of disinformation tactics, irregular fighters and Russian troops in a bid to destabilise the Donbas region.

For the most part, it worked until the new government of Ukraine launched a counterattack against the pro-Russian forces in April 2014, called the “Anti-Terrorist Operation” and was later renamed as “Joint Forces Operation” in 2018.

In response, Russia abandoned its hybrid approach for an all-out confrontation, bringing in Russian artillery and personnel under the pretext of a “humanitarian convoy” between 22 and 25 August 2014.

It eventually led to the separatists’ largely gaining control over the Donbas region even though it was still under Ukraine by technicality, and Russia still denies that they have temporarily occupied that piece of territory.

Statistically speaking, the continued Russian military operations in the Donbas region have costed over 13,000 Ukrainian lives and displaced over 1.5 million Ukrainians since 2014.

Although there were attempts at ceasefires, the first being the Minsk Protocol on 5 September 2014, there were consistent violations of the ceasefire from both sides of the board.

Whilst talks were in the process to solidify the separation lines and buffer zones, military warlords started claiming more land from the insurgents’ side, which led to the complete collapse of the first ceasefire.

The fighting became heavier and more gruesome in January 2015, which included the sanguine battles at Donetsk International Airport and at Debaltseve, a city in Donetsk Oblast province in Ukraine.

Then, on 12 February 2015, the involved parties finally agreed to another ceasefire called Minsk II, which still holds until today.

Despite the stalemate being labelled as a “frozen conflict”, low-intensity warfare is still ongoing.

According to the UN Officer of High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), there were 40,000 to 43,000 thousand “conflict-related casualties in Ukraine” between April 2014 and January 2019.

On average, ten to twelve Ukrainians are injured every month.

Although the Minsk process was established to bring a peaceful solution to the conflict, and provide grounds for dialogue, Russia has little to no incentive in changing the current status quo.

Hence, the current state of the Ukraine-Russia borders are as such:

The Annexation of Crimea

Besides inciting the destabilisation of Ukraine as a whole, Russia had also been working on another area, namely the annexation of Crimea.

Russia succeeded in annexing Crimea in March 2014 after a referendum was held and called Crimea’s return under Russia’s paw as “the return to the Motherland”.

However, the EU did not recognise Crimea’s illegal annexation, which led to the Union deciding to ban goods coming from Crimea and Sevastopol.

The US and EU also sanctioned officials, individuals, and enterprises held responsible for the annexation, as well as anyone who dealt with Crimea. Allies like Austria, Canada, and Norway echoed their sanctions.

While these sanctions did not impact the Russian economy directly, it managed to isolate Crimea economically and politically in a persistent manner that harmed the already-backwards country.

Crimea’s foreign trade plummeted by 90%. Housing prices slumped, prices of goods and services rose due to supply problems. Its annual tourism likewise decreased, with most of the tourists only coming from Russia now.

According to the prominent Russian Economist Sergey Aleksashenko’s assessment, Russian support of Crimea has cost the nation a whooping $5 billion per year.

Russian Dominance Over the Black Sea

In spite of the financial burden that Crimea has proven to become in the wake of the economic and political sanctions coming from all sides, that did not deter Putin’s determination to make good use of Crimea’s strategic location.

In the beginning of January 2017, Russia started deploying S-400 surface-to-air missile systems—which have a range of approximately 400-kilometres—in Crimea.

Since then, at least five S-400 armed battalions have been positioned in Crimea, including Kerch, Sevastopol, Feodosia, Dzhankoy, and Yevpatoria.

Additionally, in the surrounding waters of Crimea, anti-ship cruise missiles, coastal defence cruise missile systems, radar systems, and combat aircraft have also been dispatched.

With the comprehensive armament of Crimea, which sits south of Ukraine and east to Russia, it guarantees that Russia has military dominance over the Kerch Strait, and by extension, the Black Sea.

To further prove this point, in November 2016, Moscow used its installed capabilities against three Ukrainians naval vessels and detained 24 Ukrainian crew members as they transited the Kerch Strait.

Russia’s aggressive efforts only increased exponentially when it eventually opened a bridge over the Kerch Strait to connect Crimea to the Russian mainland in 2018.

The stranglehold Russia had over the Sea of Askov was particularly harmful to Ukraine because two of Ukraine’s key seaports, Mariupol and Berdyansk, can only be accessed through the Kerch Strait.

Yet, vessels must sail and navigate through these hostile waters, face detentions, shipment delays, and constant harassment from Russian authorities.

Reportedly, the obstructions in sea trade had incurred $400 million in losses thus far for Ukraine. Worst still, this can be considered an economic blockade via the sea.

Join our Telegram channel for more entertaining and informative articles at https://t.me/goodyfeedsg or download the Goody Feed app here: https://goodyfeed.com/app/

Moreover, with Ukraine sharing borders with Russia, the Donbas Regions and Crimea, the actual military deployment that surrounds Ukraine looks more akin to this:

In truth, even Putin admits that he has “all kinds” of military options to use against Ukraine if Russia’s security demands went unmet.

Although Russia’s military deployment being spread-out may cause issues when attempting to carry out a sustained operation, it is undeniable that they are capable of being mobilised in a short period of time.

The Impetus Behind the Imminent War

But one of the most pertinent questions to ask about the entire conflict between Ukraine and Russia is: Why is Russia so hellbent on ensuring that Ukraine doesn’t fall in Western hands?

The truth of the matter is that it echoes the likes of Poland and Germany during the Cold War that stretched from the 1940s to the late 1990s—

The main motivation is national defence and having a buffer zone.

Fundamentally, Ukraine is a large European country with a population of 45 million people. It’s rich in natural resources and capital, its success and failure is capable of tipping the balance of accelerating the competition between Russia and the West simply because of its geographical location in between.

From the standpoint of the US, an unstable Ukraine means that the European continent is less secure and less able to defend itself from future threats like Russia. Therefore, it motivates the US to continue to support Ukraine’s democratic path and to bolster its ability to defend itself military-wise against continued Russian aggression.

Ukraine, by all intents and purposes, is the first line of defence.

Meanwhile, Moscow seeks to prevent Ukraine from moving towards the West because it wants to keep a permanent “grey zone”.

This is evinced in how Russia has actively interfered with the Ukrainian elections and economic reform process since 2004 to ensure that a President who is more inclined towards Russia takes the main stage instead of a West-leaning variable, which was a tactic that worked for the most part, long before anyone really realised that Russia had already started on its wave of unique cyberattacks.

Even in Ukraine’s most recent presidential election, Russia had promulgated disinformation about the then-candidate Volodymyr Zelenskiy too, of how he was linked to the Notre Dame fire in Paris and he was a drug addict.

It sounds ridiculous, yes, but it didn’t stop them from trying.

The same motivation lies behind Putin’s blatant statements of not wanting either Ukraine or Georgia—formerly Soviet Union states—from joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), which was founded in 1949 to fight against Soviet aggression.

One of its founding principles states that should one of its member countries be attacked by another country or a third party, all nations in NATO will collectively mobilise its troops.

Being Vladimir Putin, with ambitions to expand Russia’s sphere of influence, fighting against so many countries at once sounds like an exceptionally foolish decision to make.

Likewise, it had been Putin’s interference during the trade deal talks between the European Union and Ukraine which sparked the Revolution of Dignity in 2014.

Revolution of Dignity (Euromaidan Protests)

What initially sparked the wave of large-scale protest in November 2013 was because then-President Viktor Yanukovych had refused to sign the political association and free trade agreement with the European Union at a meeting of the Eastern Partnership in Vilnius, Lithuania.

Being Pro-Russian, President Yanukovych had chosen to accept “bail-out” money from Russia instead of accepting a long-term trade deal, receiving $2 billion first out of a $15 billion package, which was perceived as a move to seek closer ties with Russia.

These protests lasted for months, to the extent where clashes between the protestors and the riot police descended to violence, resulting in the deaths of nearly 130 people, including 18 police officers.

And as history will tell you now, the protestors had won.

On 21 February, an agreement between President Yanukovych and the leaders of the parliamentary opposition was signed, calling for an early election and the formation of an interim government.

The interim government, led by Arseniy Yatsenyuk, proceeded to sign the EU agreement in Yanukovych’s stead.

Afterwards, Petro Poroshenko won the Presidential elections by a landslide, and Yanukovych fled the country the day before he was ousted and impeached by the government.

Yanukovych even pleaded with the Russian Federation for assistance, which they could have done under the excuse that the previous protests and later elections was an illegal coup. The Kremlin was both in favour and against the notion, but decided to abandon that prospect in the end, in favour of focusing their attention on the Russian invasion in the Donbas region.

The Economic Costs

Judging from Russia’s economic situation though, an all-out war should be unlikely.

First and foremost, while Russia would like to conceal its own economic information through omission, the long-standing sanctions that have been placed on Russia have affected its economy.

Throughout the years, the Obama Administration and the EU have frozen Russian companies’ access to Western financial markets, which have also made Western companies wary of investing in Russia.

In general, western financial institutions have been banned from issuing loans with maturity periods exceeding thirty days for several of Russia’s biggest banks and companies, which does an excellent job in ensuring that Western creditors avoid entering long-term operation with their Russian counterparts at all costs, though payments were not impeded.

The effects were slow-going, but by the middle of 2016, the inability of many Russian banks and companies to raise any funds from the Western capital had caused a painful impact on the Russian economy, and placed pressure on the Russian Central Bank to provide the missing liquidity.

A decision which Putin is reluctant to make, as his main goal is to rule a neopatrimonial autocracy, wherein his regime sustains the loyalty of narrow elites through a distribution of benefits and spoils, that will in turn continue to support his reign.

However, in maintaining such a system of governance, wealth tends to be concentrated in the hands of a select few. For the same reasons, protests have risen in waves, calling for pension reforms or an increase in qualitative living, but this has only led Putin to become more repressive and severe against his critics.

But this also means that sanctioning of individuals—of which the US and EU has done—is a particularly effective tactic. When eight Russian oligarchs were sanctioned in April 2018, Moscow was shocked and its stock exchange fell by 11% that day alone.

If the war does happen, you can at least be certain that it will take a toll on the country financially, except how quickly the fallout will be is unknown.

Likelihood of the War Happening

Shots will be probably fired as a warning.

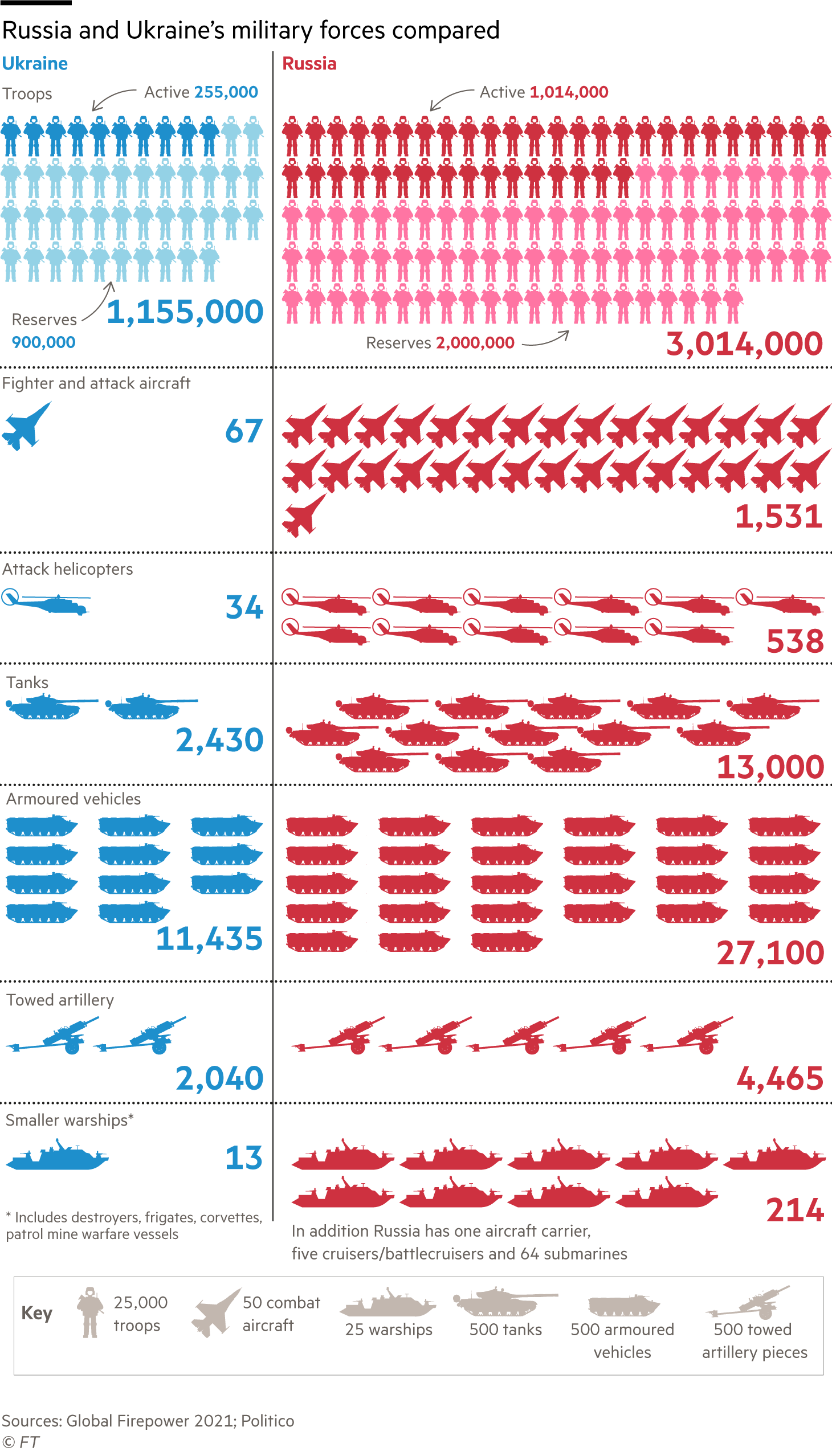

When comparing the military prowess of Russia and Ukraine, the chances of winning by numbers falls heavily in Russia’s favour.

However, this is not taking into consideration how the other nations will react in response to the invasion of Ukraine, and besides re-claiming what was supposedly Russia’s old lands, what does really Putin stand to gain in this war?

Honestly speaking, he stands to lose more by taking an aggressive approach in times where sovereignty is of great importance, and when the world is now more educated and wary of starting large-scale wars.

Rather, his aggression towards Ukraine seems more like a tactic to use the buffer country as a bargaining chip to exchange for the easing of the financial and economic sanctions placed on Russia and Crimea.

Alas, this is all just speculation on my part.

Readers, you are now duly informed of the conflict between Ukraine and Russia in a somewhat simplified manner!

Read Also:

- 17YO Allegedly Committed Suicide After Being Deserted by His Parents Twice

- Appeal of Drug Trafficker on Death Row in S’pore Adjourned Again

- 6 Religious Groups Hold Inter-Faith Prayer Session at Greenridge Crescent Canal

Featured Images: Shutterstock / Alexandros Michailidis & Sasa Dzambic Photography

Would you be jailed for being half-naked in public? Well, the answer will shock you. Seriously. Watch this to the end and you'll understand: