On Wednesday (22 June), Zakir Hossain, a Bangladeshi migrant worker who has been working in Singapore for over 19 years, took to Facebook to voice his plight about being deported back to his home country because his work permit wasn’t renewed.

Confusion Over the “Adverse Record”

Apparently, when his company’s Human Resources (HR) department tried to renew his permit, the application failed, with the system reflecting this message:

“This worker has an adverse record with a government agency.”

From what Mr Zakir recalls from a response that Minister for Manpower Josephine Teo made during a parliament session, if an “adverse record” is listed as the reason for a non-renewal, it should mean that the worker is aware of the offence they committed because “enforcement actions would have been taken against [them]”.

With that context in mind, Mr Zakir tried to repeal the non-renewal, first going down to the Police Cantonment Complex to search for this “adverse record”, except to come up empty.

To his own knowledge, he hadn’t committed any crimes either.

Hence, in the little time Mr Zakir had left in Singapore (his HR managed to secure him a week of extension), he gathered help from a few Non-Profit Organisations (NGO) and select individuals to write an appeal letter to the Minister for Manpower Dr Tan See Leng and Senior Minister of State Mr Zaqy Mohammad, on his behalf.

Later, a group of organisations requested for a closed-door session with Dr Tan, though the Minister only agreed to a meeting with one person from the group.

MOM: It Was An Administrative Error

Mr Zakir was correct in assuming that he hadn’t committed any offences.

However, the most recent reply came as a greater shock.

MOM confirmed that there was an administrative error, and the system shouldn’t have reflected him having an “adverse record” as a reason for the non-renewal.

Instead, it should have been “ineligible”.

That’s worse than having a black stain on your record, because it means that there’s no way to overturn this judgement. Mr Zakir will never be able to work in Singapore again.

Having exhausted all options of appeal, he took to Facebook with an open letter.

After mulling over the reasons why he would be considered “ineligible” to stay in Singapore, a place that he’s essentially made his home in the last two decades, his only conclusion is that it was his activism that landed him in this place.

After all, he has been brutally honest about the circumstances surrounding a migrant worker’s life in Singapore, consistently advocating for the betterment of their living and working conditions, plus a greater acceptance for migrants as part of the Singaporean society.

He proceeds to list his contributions: organising literary and art activities for both the migrant and local community, such as the Migrant Art Festival & Exhibition, Mental Health Awareness and Wellbeing Festival, and Slam Poetry.

He created Migrant Workers Singapore, where he gave his fellow migrants a place where they could speak out and find a sense of belonging among like-minded people.

He showcases how his activism in Singapore is a well-known fact, such that he’s been invited by TedX Singapore, local universities, and polytechnics to have panel discussions about challenging stereotypes imposed on migrant workers.

Mr Zakir implicitly argues that he shouldn’t be penalised for lobbying for equal treatment and talking about social issues.

He’s written angry poetry about the treatment that migrant workers receive, especially during the pandemic period.

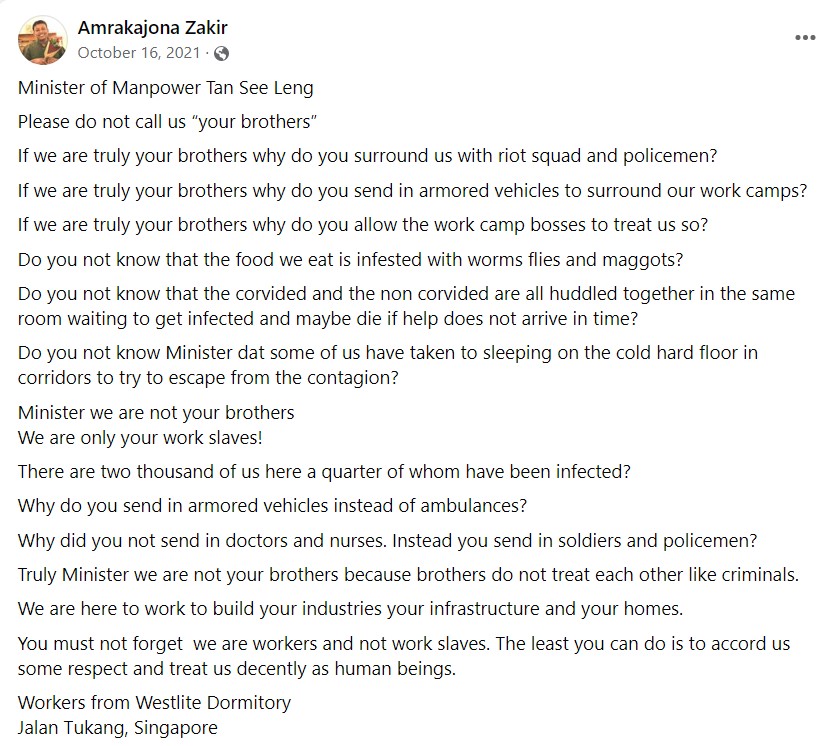

One poem in his collection that really stood out from the rest, is entitled Please do not call us ‘your brothers’, conveying the ever-present problems and hostile prejudices, except now the pandemic has catalysed and exacerbated the situation.

In the poem, Mr Zakir pens down the terrible conditions in the dormitories, where the buildings were overcrowded and thus more susceptible to the spread of disease, the poor management system, lack of medical benefits, and the poor treatment where migrant workers are viewed as “work slaves” instead of actual human beings.

One of the lines even goes, “Truly Minister we are not your brothers because brothers do not treat each other like criminals.”

The entire literary piece is rather provocative and can easily feed into the frustrations and anger that the migrant workers are feeling.

After all, we can’t deny that we do treat our migrant workers differently, and some of us hold xenophobic inclinations, whether unwittingly or not.

For the same reasons, Mr Zakir wonders if his sudden deportation is the price of his activism, for raising concerns about their employment and living conditions, and he was just being silenced as an example for the rest to see.

MOM: Ineligibility due to False Statements and Misinformation

Ever since the Facebook post has been published, it has received more than 450 responses, and been shared over 200 times. The comment section is a mix of sympathy, anger, or bafflement.

Many were sad or enraged to see him leave, feeling helpless as they couldn’t render any assistance. Others found his departure natural; while it isn’t well-documented, there have been instances of activists being silenced.

Some believed that he deserved this ending, for pushing the boundary line too much, and for stepping on the toes of the Government

The MOM was immediately alerted to his open letter, as they proceeded to release a public statement regarding the non-renewal of Mr Zakir’s work permit on the same day.

The Ministry first corroborates that Mr Zakir has been a social activist for a long time, in the 19 years that he has resided in Singapore.

Therefore, it should be evident that it wasn’t his activism that made him ineligible, because they have renewed his work pass many times in the years prior.

“We draw the line, however, when public posts are misleading, false or deliberately provocative.”

Join our Telegram channel for more entertaining and informative articles at https://t.me/goodyfeedsg or download the Goody Feed app here: https://goodyfeed.com/app/

Remember the poem above?

It was written on 16 October 2021, and the Ministry took particular offence when he called the migrants “work slaves” and the dormitory “work camps”.

In Please don’t call us ‘your brothers’, Mr Zakir also alleged that the dormitories were surrounded by soldiers and armoured vehicles, and that the food was “infested with worms flies and maggots”.

The MOM clarified that his poem was a “false characterisation” of the situation.

The police were deployed to the dormitories as a precautionary measure, but they never surrounded the compound. In fact, they were stationed there so that the migrant workers had a direct line of contact to address their concerns.

More importantly, Mr Zakir never resided in Westlite Tukang, despite signing off on their behalf.

An argument can be made about artistic liberties, but the main issue that MOM had with that poem was that it could have “inflamed [the migrants’] emotions and possibly caused incidents of public disorder.

Owing to his long years as a social activist, Mr Zakir does hold some influence over the migrant and activist community, so his poetry would have reached an audience of a considerable size.

The MOM states that it was fortunate that the real residents of Westlite Tukang had personally witnessed their employers and dorm operation being serious about addressing their concerns, which allowed the migrants to keep a level head.

Furthermore, MOM asserts that they, alongside other government agencies, have “taken considerable pains to safeguard the well-being” of the migrant workers and reduced the risk of transmission.

To prove their point, they pulled out the statistics, where the mortality rate among migrant workers was only two despite the numerous outbreaks in 2020 when the vaccines weren’t created yet.

Once the vaccines were available, MOM ensured that the migrant workers were vaccinated, were spaced out enough to reduce the risk of transmission, and conducted routine checks.

Additionally, the Ministry stressed that the migrant workers were paid even during the Circuit Breaker period. Back then, non-essential jobs (like construction) were brought to a halt, and it couldn’t possibly be done from home, and the number of people required at construction sites would have easily exceeded the imposed restrictions.

“The ability of a foreigner to work in Singapore is not an entitlement,” MOM added.

Since Mr Zakir’s work permit has expired and he no longer holds a job in Singapore, he has “overstayed his welcome”.

Needless to say, there’s no love lost between the MOM and Mr Zakir.

Read Also:

- Student Jailed for Driving Dad’s BMW to Speed in KPE During Circuit Breaker

- S’pore Confirms 1st Case of Imported Monkeypox Case Who Had Gone to 3 Food Establishments

- Property Management Firm Apologises After Allegations of Discriminatory Hiring Practices

- Parkroyal Pickering S’pore Apologises After Rejecting Same-Sex Couple from Hosting a Wedding in the Hotel

Featured Image: Facebook (Amrakajona Zakir)